Dear Family and Friends (not necessarily in that order),

Last fall I had so much fun when I got to talk about my mother, Rhoda Bailey Warren's autobiographical book, "Appalachian Mountain Girl" at Belmont library's book club, and I learned a lot while preparing for the 30 minute talk. I mined a little deeper (if you will) into her Bailey family story for the years covered by her book, 1930 to 1941. You might be interested in some of what I found. You must definitely be interested that I have figured out (OK, with lots of help from Dale) how to have a blog at all.

Here it is--Your Mama's Blog.

I needed to re-read the book carefully,

because believe it or not it's been 20 years since it was published, in 1998. I was taken by surprise by a strong new understory I "heard" this time--call it my added years of wisdom or finally listening to my mother's voice, but this time there it clearly is--the story she doesn't tell out loud: the very dark story of the effect the Great Depression had on her family. Her family was just one of millions of American families who walked through the years of dark hardship with courage and strength and positive energy, of course. Rhoda conveys this to us without complaint or dwelling on the hardships that were there, she seems only to tell us of the kindness and intelligence of her beautiful neighbors--but there it is anyway. Waiting for me to notice.

What am I talking about?

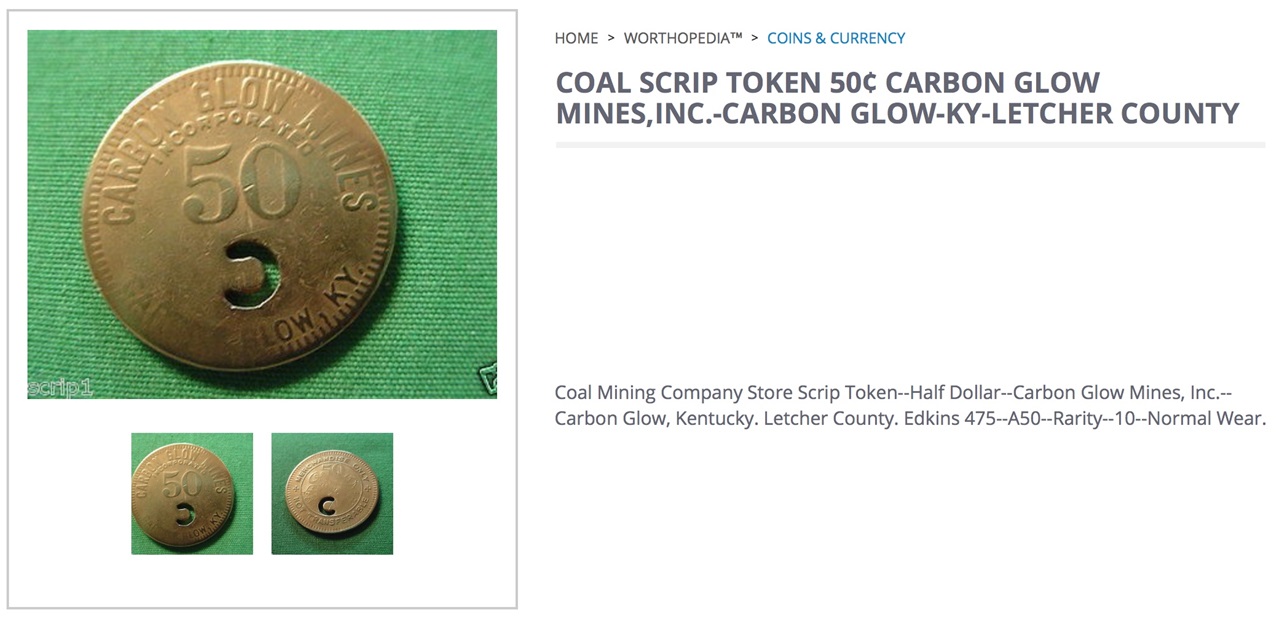

In the first chapter Rhoda tells us her setting and time, "in the dog days of August, 1930, at Corbin Glow, one of the newest and largest mining operations in southeastern Kentucky...".

and just that one phrase tells us a whole story's worth of information.

In 1930 when she starts her story, Rhoda Mae Bailey was 8 years old. She lived with her parents Frank and Laura Bailey and four siblings, James, Frank, Irene and Eugene. Her father was a coal miner with Carbon Glow Mining Co., near Letcher, KY. (By calling it Corbin Glow I think Rhoda conflates Corbin, KY, a nearby city, with Carbon Glow, the name of the mine where her father worked.)

Now, let's back up.

Even I remember from high school history --the Great Depression? 1929! Put that fact securely in the back of your mind while we chat here. And while you're putting things, put "Appalachian Mountain Girl" by your chair so you can glance over that first chapter tonight. All will become clearer with a new read, I 'm confident.

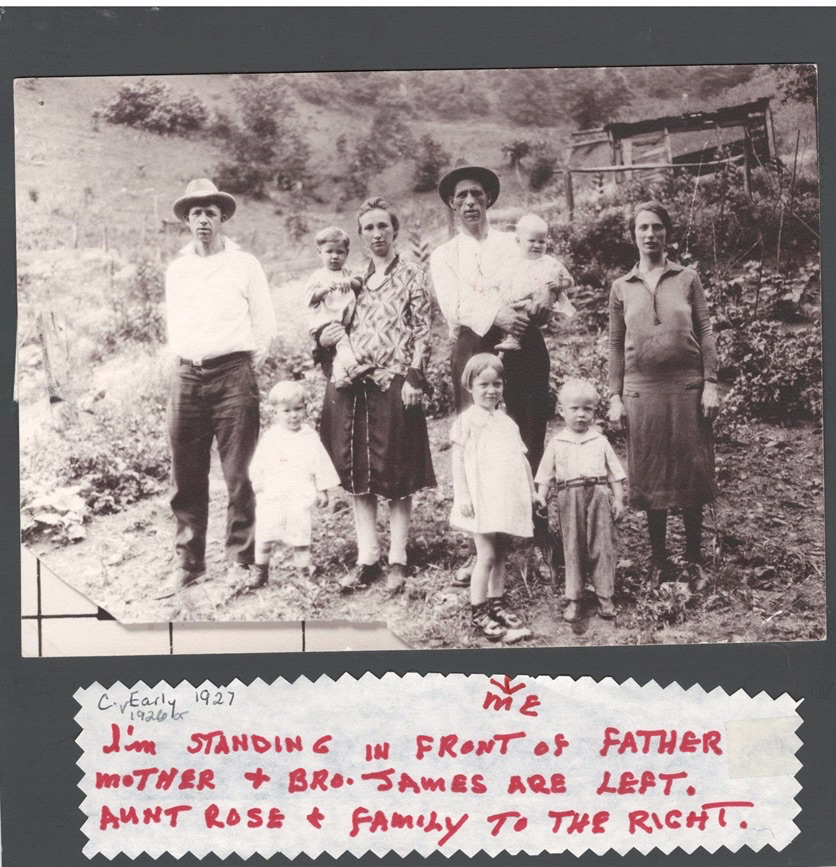

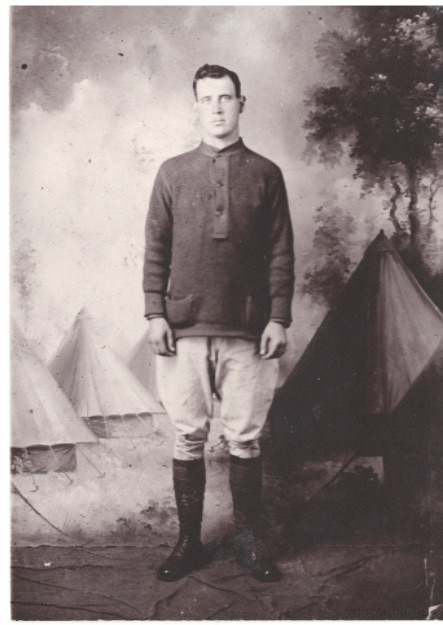

Now, let's back up even farther and start with her father, my grandfather, Frank Bailey. He was born in May 1895 on a farm in Frozen Creek, KY. (Point of interest, perhaps: Rhoda's eventual husband Howard Warren was just one year younger than her father. Howard was born in May of 1896.)

Frank

returned home after WWI service, married Laura Johnson and by 1927, the probable date of the photo at the top of this page, they had 3 children and another on the way. I believe the picture was taken at his family farm in Frozen Creek with his sister, Rose, and her family, before he ever went to work in the coal mines.

With a growing family to support and hearing stories of money to be made in the newly opened coal mines, it looks like an ambitious Frank Bailey left the struggling family farm for a new life in Letcher, KY, working at Carbon Glow mines.

Now Rhoda is telling us

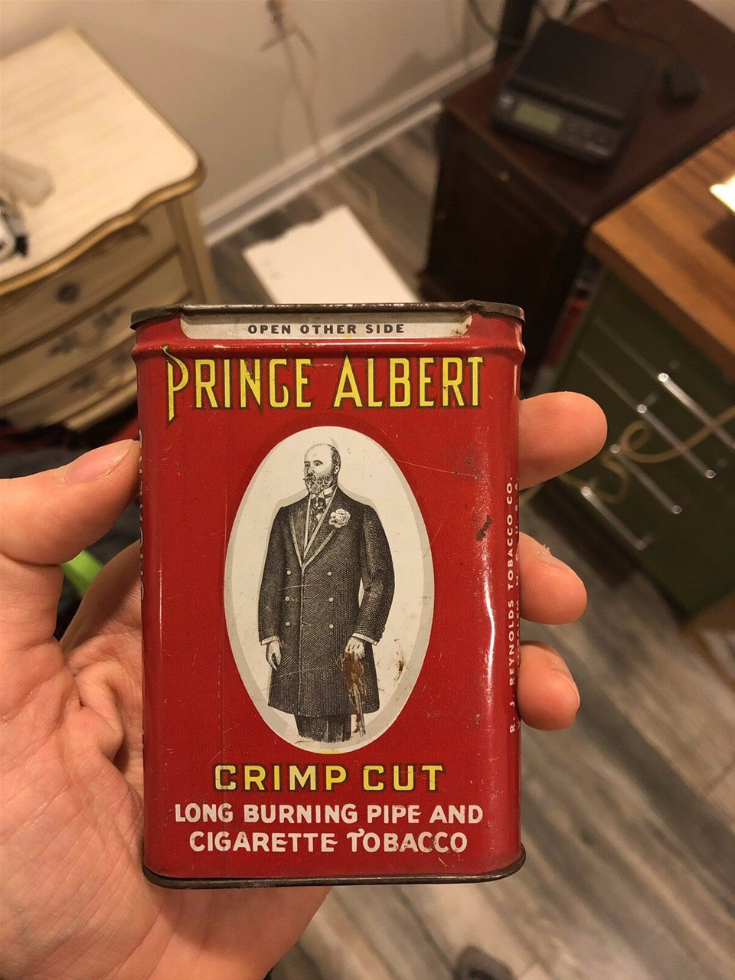

that already, just three years later, in 1930, mining has paid so well that her dad can take $200. savings from a red Prince Albert tobacco can hidden under his bed to make a down payment on a house. That's the equivalent of $3000. in today's money they had managed to save in just three years. At his wife's urgent request to leave the dirty, dusty coal mine settlement, Frank buys them their own home away from the Carbon Glow camp, even though the move means now Frank will have to walk an hour each way to work. Frank Bailey obviously loved his wife and family very much.

Note for our younger readers:

There was a time when red Prince Albert tobacco tins were ubiquitous. When their contents had been savoured, the empty tins were commonly used to store things...a roll of bills would be safe and dry, or screws or bolts, or maybe some dried beans from your garden you're saving to plant next year.

But now, ever more rapidly after 1930,

the domino effect of the Depression's financial landslide reaches the coal mines as less and less coal is needed by flagging industries. More and more days there is no work for the miners. And for them, no work means no pay.

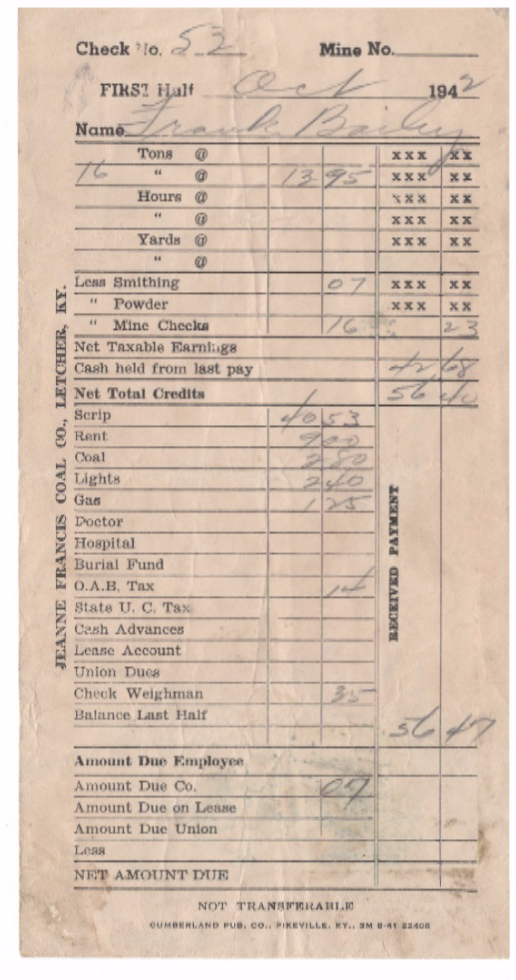

Miners had, back before their labor unions were started, notoriously dangerous and unprotected working positions. The company usually owned their home for which they paid the company rent. The company owned the grocery commissaries where workers bought food with scrip they were paid that could ONLY be spent at that company's store. The company charged back each miner for checking their dug coal for purity and even for sharpening the tools they used to work with (see the "smithing" fee on the pay stub below.) This worked fine when there was plenty of work but when there wasn't their finances rapidly collapsed on the workers.

This pay stub is one of my favorite

pieces of family ephemera. The date, October 1942, is the month I was born when Frank Bailey first became a grandfather. It's an example of all the subtractions the miners' employer was used to taking from his pay. Certainly money for a "Burial Fund" would be important if you were providing unsafe working conditions for your workers!

Three years later, in 1933, Carbon Glow Mining Co. completely closed its doors.

There was suddenly no pay and at that time certainly no unemployment compensation for workers. The company closed their grocery store. There would have been no garbage pick-up, no coal delivery or electricity to their homes--all those had come from the company, now shut down.

To compound this for the Bailey family, they had just bought their own home with their savings...now there's no income for house payments, and the house, located in an area of devastating economic collapse, is probably not saleable. I'm imagining Frank and Laura lost their savings and equity in that house, the house that Laura had called "the prettiest house on earth" when she first laid eyes on it. The next US Census report in 1940 lists them as renting a home again.

We can try to picture what this would have been like for Rhoda

As a bright 11 year old, she carried a lot of responsibility as the oldest of her seven siblings. She would have seen her parents' worried faces and overheard their tense conversations and arguments at night. She took care of the little ones and surely worried about the lack of food. She says about this whole situation only this one sentence:

"Father, hoping to stave off another winter like the one we'd just had, had staked off a piece of mountain owned by the coal company" where he planned a garden to feed his family.

Frank bartered with friends and neighbors for seeds and plants. His sons, James, Frank and Gene, aged 9, 8, and 4 respectively, were enlisted to weed and to de-bug the potatoes in the huge plot. Irene surely would have helped. Rhoda, we read, emphatically declined to participate in the gardening effort at all.....

The only time time Rhoda comments about what this Depression meant to her personally was in this chapter. Here's the paragraph:

"One day, a little after daylight, still wearing a long cotton nightgown and wrapped in one of Mother's tattered housecoats, I took my breakfast--a hot biscuit, flat and heavy because there was no baking powder in it, soaked in molasses--to one of the big swings on the front porch. For the thousandth time, I stared at the little streams and gullies that lay hidden by day in deep green entanglements on all the mountainsides, but were at this hour softly defined by rising mist."

"Mmmmm, beautiful," I say to myself wanting, to be on that swing with a warm, sorghum-saturated biscuit in my hand....but then, "Wait, WHAT? She says here's no baking powder? I remember, no money for food....this IS a bad time Isn't it?"

But nary a glimmer of this did we ever ever hear from Rhoda herself.

The Eloquence of One Flat Biscuit

(Well people, this is Sue after all--of course there will be talk about food. I think you really should have expected this. )

In a nice coincidence I was reading Ronni Lundy's beautiful cookbook, "Victuals: An Appalachian Journey, With Recipes" when I was thinking about conveying all this family news to you. She was born near Letcher in Corbin, KY and is a popular author and authority on southern cooking and food traditions. The beautiful pictures of country Kentucky food alone in this book are worth a trip to your library which is where I first saw it.

It was Lundy's special section on its production that put me on to sorghum syrup. For some reason I always thought of it, if ever I did think of it, as a more bitter version of molasses, but I can tell you now it's not. It's lovely, much lighter, more like a cross between honey and molasses. It is made from sorghum stalks, not sugar cane as true molasses is, and nowadays it has had such a resurgence of interest that lots is made by artisanal sorghum mills and there are summer Sorghum Festivals held in areas throughout the mid-south.

We can be pretty sure, since it is the locally produced "molasses" of their area (sugar cane is grown and produced farther south since it requires hotter weather), that it was sorghum molasses in which Rhoda's warm flat biscuit was soaked. So, to get myself in the proper mood and frame of authenticity here, I ordered me a jar of the real thing right from Oberholtzer's Sorghum Mill in Liberty, KY. (It was available on Amazon, of course, isn't everything?).

When it arrived I made a batch of biscuits. Then I did as Ronni Lundy instructed as to the management of butter and sorghum syrup relating to biscuit enhancement: She sez, "The proper way to have sorghum--as any country girl or boy worth his molasses will tell you--is to mash it and cream it with a soft blob of butter until it makes a smooth gold-bronze spread which you then daub a bite at a time on hot biscuits." She swears this results in a much tastier spread than layering the two on your biscuit one on top of the other. Who am I, a half-Northern person, to argue?

Chet Atkins, the country music star, told Lundy, "I still mix my molasses that way with the butter. Oh, yeah, yessir, I still do that--and I've gotten so I fix a little peanut butter with it, too. Mix it up just like the butter."

We gave Chet's idea a try here on Redfern Dr. Nice. It's on the order of the peanut butter and honey sandwiches we used to have for lunch at Wyoming Central School.

In the Jewish tradition, holiday foods are used to relate and remind of history,

to help people remember important moments and achievements of the past. Fried foods like potato latkes, for example, are traditional at Hanukkah to commemorate the miracle when a small one-day amount of oil miraculously kept a Menorah alight for eight days for the Maccabees when they most needed it back in 160 BCE.

So maybe it would be good if I made a batch of biscuits for our next family gathering. I'll put out butter and sorghum syrup and we'll blend the two on our plates before smearing. And as we enjoy them we will think of our family and their hard work and courage in that hard hard time. And we'll remember to give thanks for all the small pleasures we have and take for granted, that right now, anyway, we can afford baking powder again.

Thank you for reading my blog.

Do you have comments or suggestions for next time?