Welcome to Sue's Blog the Second, in which we will explore these family stories:

- Great-grandfather Woodford Bailey raised horses and distilled moonshine whiskey in the Kentucky county that was called "Bloody Breathitt" because of its 50 year history of deadly feuds.

-His mother was Jennie Runyon Bailey whose father was an American Indian. (So, dear family, when you see your DNA results say hello and welcome to Grandma Jennie.)

-We'll read about our family's thread to the beginnings of NASCAR.

-And the nicest surprise: Our guest writer for this and the next section of The Sue Blog is Rhoda Bailey Warren herself, so we'll be reading these stories in her own words.

Ready??

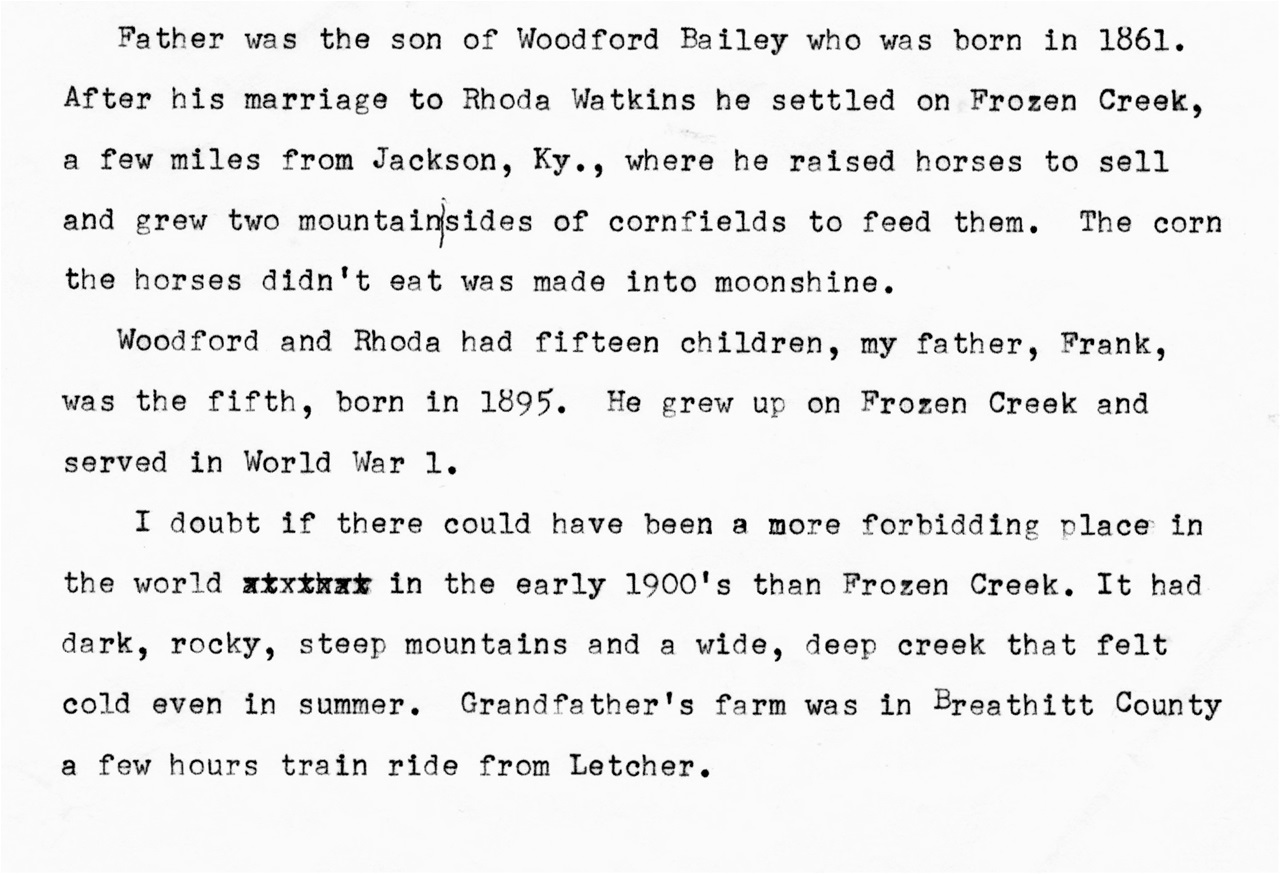

I kept a lot of Rhoda Bailey Warren's papers when we sold her house. The manuscript of her book, "Appalachian Mountain Girl," laboriously hand-typed with the business-like gray Smith Corona on our dining room table, certainly. At that busy time I just stuffed all her papers into file folders and stored them in our basement. Recently, when I pulled them out to show you I found a chapter, an "out take" of the book, with short biographies of both her parents and a long lovingly-detailed development of the school she attended in Letcher, KY, the Stuart Robinson School--three things that were most important to her childhood. This was labeled "Chapter 3."

So this time let's look at what she told us about her father's Bailey family, and in our next blog we'll read about her mother Laura's childhood as an orphan.

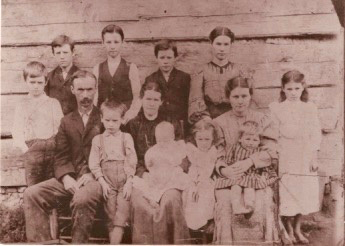

Here they are: Great-grandparents Woodford and Rhoda Watkins Bailey, with 11 of their 15 children. Rhoda's father, Frank, has the serious little face in the very back on the left. The photo is labeled "Frozen Creek c. 1920" but Frank looks only about 13 or 14 to me, which would make it closer to 1910.

Now, let's step back one more generation.

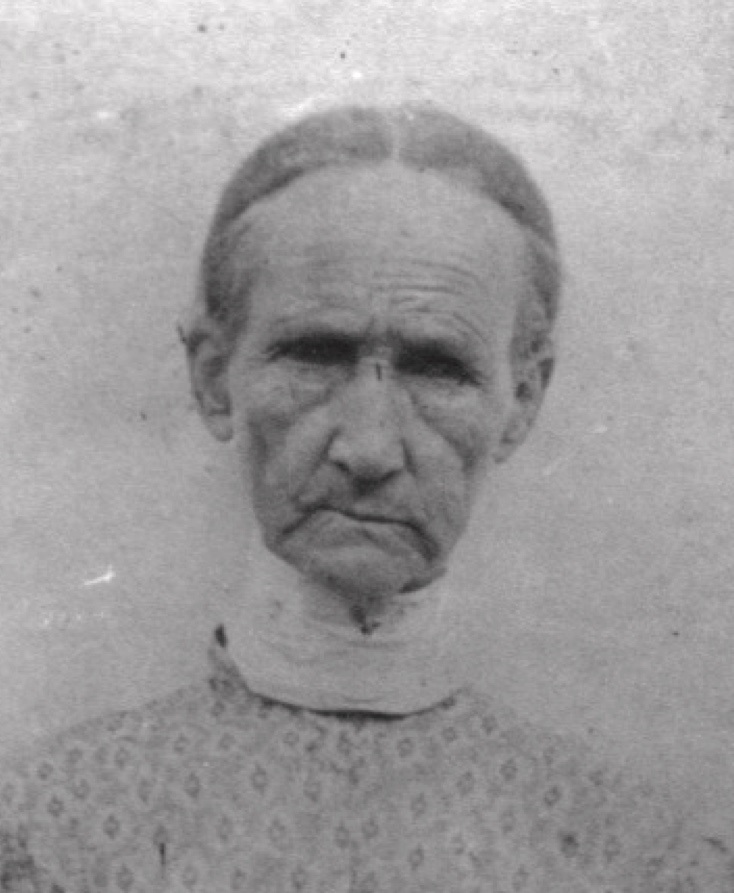

Here is Jennie Runyon Bailey, my great-great-grandmother. Just scroll back to see the strong facial resemblance to her son Woodford.

Jennie's father, my great-great-great grandfather, was an American Indian. Which pleases me to no end. When the next Mayflower-sailing Johnny-come-lately acquaintance starts smugly intoning his family history to me I shall assure him that my ancestors were no doubt right there at the gangplank to greet his folks with a warm blanket and a nourishing squash casserole.

Large families like Woodford Bailey's, which are pretty unthinkable to us now, were common in that time and place. Many hands make light work and all that, and there certainly was plenty of work to be done. Other conjectures such as a lack of social life and outside entertainment we will leave for your own musings. Be sure to factor in the privacy factor in the small, usually four rooms max, size of their houses when doing so. Since these early homes were comprised of a few rooms, a covered well in the yard and an outhouse out back, Harry Caudill wittily refers to them as homes with "4 rooms and a path."

But I digress...The important facts for today: Rhoda tells us that in the early 1900's her grandfather, Woodford Bailey, lived on the cold and forbidding Frozen Creek in Breathitt County, KY, where he "raised horses to sell and grew two mountain sides of cornfields to feed them. The corn the horses didn't eat was made into moonshine."

Here's what I learned:

Whiskey-making came to Appalachia with the first Caucasian settlers in the 1700's. Their ancestors from Ireland and Scotland knew how to make whiskey from grains like barley and rye, so it was a simple transfer of knowledge to begin making whiskey from local corn as a method of preserving their excess corn crop for later use or trade.

It was exactly as Rhoda told us: They raised corn and what they didn't need for themselves they processed and sold or bartered to others.

Income from liquor production was an economic necessity for their families and in the mountain farmer's mind exactly the same as selling dried beans or hay or jam from her fruit. It was a homegrown product they felt they deserved to be able to sell for needed income without the penalty of extra taxation.

It's simple economics. One source points out that one horse can carry four bushels of shelled corn out of the mountains to market, but when the corn is distilled into whiskey the equivalent of twenty-four bushels can be transported by the horse and sold for more profit. So naturally, the best return for the work is the "added value" concept of making whiskey from part of one's crop.

And it WAS work. While we've been led to picture moonshiners as ne'er do wells laying around in the woods tellin' stories around the still, in fact carrying sack after sack of corn and sugar far up into the mountains and then heavy barrels of whiskey back out again, all over narrow, rutted forest paths was back-breaking work.

US government's decision to tax liquor production was at first based mainly on the need to raise money to pay for a couple of wars. As you can see, I'm hedging over to the side of the moonshiners here. (It's called "moonshine" by the way because it needed to be produced at night so law men were not able to easily spot smoke rising from the stills.) Certainly I'm oversimplifying some complicated historical factual developments--but this is family after all. The whole story is pretty interesting reading if you care to Google around and look into it. I've put links at blog's end.

But to sum up, friends, the entire government-taxing-our-whiskey idea was viewed poorly by Appalachian mountain producers. And by "viewed poorly" I mean there're stories of moonshiners shooting representatives of the law who came to wreck their stills, and feeding their bodies to the pigs.

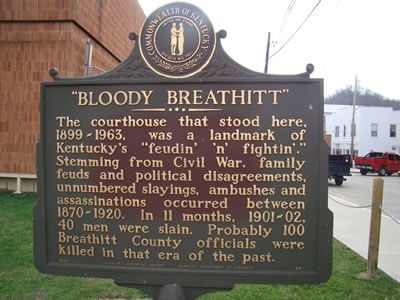

The bloody fighting over the imposition of a tax on their production started way before Prohibition in the '20s and just added tinder to the already intense political, inter- and intra-family feuds--feuding being a polite name for bloody murders and social mayhem-- which had continued in Breathitt county and others surrounding since neighbors disagreed over stands on the Civil War. These were hit and retaliation wars, essentially gang wars.

This state marker in Jackson describes the horrific extent of the "feuding": 40 people in rural Breathitt were deliberately murdered in just 11 months in 1901. That's as if 2055 murders occured in Boston in less than a year-- the same percentage population-wise. My little grandparents-to-be, Frank and Laura, were busy children trying to grow up in a place where hate and carnage was going on like a war zone.

While you meditate on all that, I need to make a rapid shift here.

(Get it...Rapid shift?? YEEEE-Ha!! When I'm good, I'm good...)

I promised you a NASCAR story and so it shall be.

Prohibition, which came along in 1920, actually increased demand and prices for homemade liquor. At the same time automobiles became available which enabled a more, um, efficacious egress from the distillation work scene upon necessity, if you see where I'm going here. The get-away cars were customized for high speeds on the mountain roads. Soon, friendly races around cleared fields were scheduled to show off the skills of the best local auto modifiers and drivers--and from there it's a straight line to NASCAR--you can read about it! But all of you thinking 'Dukes of Hazzard" here (and I know who you are Andrew Mearns) you can stop right now. Think about it--if you are transporting illegal goods, hoping to elude the law, you want your car to be as unobtrusive as possible. The plain black Ford exterior was always carefully preserved, and the powerful new engine inside did not ever show to the observer, just purred along quietly until it was needed. There were no shiny hubcaps or red exteriors to attract the attention of The Law, the Dukes family vehicles notwithstanding.

Let me very rapidly assure you that I personally have learned nothing of any trouble that my great-grandfather had with the law at any time. Ever.

But the fact is, Rhoda did tell us Woodford Bailey made moonshine. Which implies nocturnal production. Nocturnal to avoid notice by local, or hey, even federal, law enforcement officers.

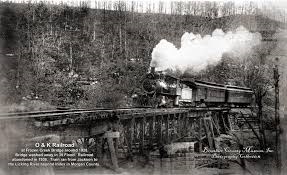

And that railroad track was right there.

I'm just sayin'.

What do I think?

In all the material I saw (and I refer you especially to the video link below) there was only respect for the work ethic of the Appalacian whiskey distillers, the moonshiners, how hard they had to work to provide for their families in a deeply economically stricken area. We have only to look at the photo of Woodford Bailey's handsome healthy family to know that love and care for them came first. And a hundred years later we see his example still living strong. I'll drink to that!!

Some good sources:

This is my favorite: a short video interview of three men who participated in the moonshine process, in differing capacities. They are knowledgeble and fun to listen to.

Harry M. Caudill's book "Night Comes to the Cumberlands", 1963, is very helpful. Tons of information about moonshine production, its economic importance; early mountain families and their farming techniques, and the decades of feuding that went on in the area. Everything about our family except their actual names is in this book.

also "Bloody Breathitt: Politics and Violence in the Appalachian South" by TRC Hutton

I finally read, "Hillbilly Elegy: A Memoir of a Family and Culture in Crisis" by J D Vance. If there could be a sequel to Rhoda Bailey Warren's book this would be it. What took me so long??

My cousins Dave Bailey and Kandie Parker have done extensive Bailey family genealogies-- a wonderful gift to everyone of us. Thank you.

The recipe for this time:

Hootenholler Whisky Cake

of course.

First a disclaimer: No connection to Kentucky here. Even the "whisky" is Scotch you can tell by the spelling with no "e". We'll make ours with good KY bourbon whiskey-with-an-E and a dollop of sorghum instead of the called-for molasses. NOW it's authentic.

The recipe is from "The I Hate to Cook Book", a best seller back when I married in the '60's. Peg Bracken, the author, turned cooking into a fun and funny chore for newly-domesticated 20 year olds like me and my friends who grew up in kitchens governed by the prim Betty Crocker, speaking tersely from her red and white 5-ring tome on the pantry shelf, and by our mothers looking judgementally over our shoulders.

Under Betty's spartan tutelage the only remotely zippy ingredients in our growing-up kitchens of the '50's were the small metal box of French's powdered sage to be added to each Thanksgiving's turkey stuffing (how many years did that one box last??) and another box of the more rakish paprika which was ONLY used to be strewn artfully over deviled eggs. Betty did not run to the racier thyme or even garlic...and certainly not to wine or bourbon.

But then we girls married and found ourselves far from Betty and our mothers in our new kitchens alone with our shower-gift copy of "The I Hate to Cook Book". And there was Peg Bracken instructing us to bake this cake:

"First take the whisky out of the cupboard, and have a small snort for medicinal purposes. Now cream the butter with the sugar, and add the beaten eggs." I loved this! The NOT Betty Crocker.

We latched right on to Julia Child, too, when she came along with lots of wine and all those herbs and copper pots and saute pans....Rhoda's cast iron skillets are back on my the stove now, but they spent a long time in the closet I admit.

Here's a link to more info about Peg Bracken, including the recipe for our Hootenholler Whiskey Cake:

https://www.nytimes.com/2007/10/28/weekinreview/28bracken.html